An Interview with Me, Will Wright!

- ACME Hi Fi

- :

- Games

- :

- The Art of Fun

- :

- An Interview with Me, Will Wright!

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

This article was taken from the September 2012 issue of Wired magazine. Be the first to read Wired's articles in print before they're posted online, and get your hands on loads of additional content by subscribing online. For almost 30 years, Will Wright's creations have attracted people who never played video games, enthralling hardcore fans while making rabid players out of novices. The secret: in Wright's worlds, there is no win or lose -- just the game.

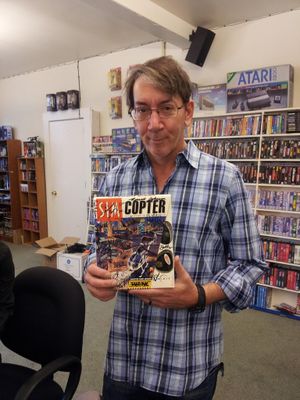

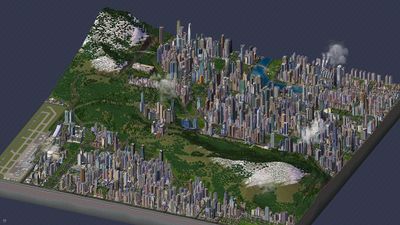

Will Wright with a copy of Sim Copter Will Wright with a copy of Sim Copter He's best known for creating the Sim franchise. These unlikely blockbusters -- more than 180 million sold so far -- drew on the works of arcane theorists, urban planners and astrophysicists, yet they were addictive. They thrived thanks to what Wright calls possibility space: the scope of actions a player can take. Most games give a narrow possibility space: do you want to kill bad guys with bullets or grenades? Take the door on the right, or the one on the left? Wright and his team at Maxis, the development studio he cofounded in 1987, blew past those constraints, creating an infinitely flexible world limited only by the skill and imagination of the player. In Wright's best work, players have so much leeway to determine their objectives that the distinction between player and designer blurs. In 2009, after more than 20 years at Maxis, Wright stepped down to form Stupid Fun Club, an entertainment-development think tank. He met Wired in Stupid Fun's Berkeley studio to review his career, hint about upcoming projects, and speculate about what the future holds for us all -- gamers or not.

Wired: How did you start with computers?

Will Wright: I was involved in building models, which evolved into robots. I got my first computer when I was 20 and taught myself programming to connect to my robots. That's what sucked me into writing software.

When did you go from playing around to saying, "I'm going to be a game designer"?

Around 1980, I was living in New York, and there was one store in the city that sold the Apple II. They had a few simple games and I started thinking, "Maybe I should try making a game, because then I can make my computer expenses tax-deductible." Then I bought a Commodore 64 in 1982, and dedicated myself to learning everything about it.

Has there been a common thread that runs through your career?

It's really been about trying to construct games around the user. How can you give players more creative leverage and let them show that to other people?

That's in your first game, 1984's Raid on Bungeling Bay, but it's almost invisible.

It's very action-oriented; you're a helicopter fighting this military-industrial complex. You bomb ships, tanks, planes and factories.

How did Bungeling Bay lead toSimCity?

I wanted Bungeling Bay to have a world large enough to get lost in -- I was having more fun building worlds than blowing them up.

The game became a blockbuster and passionate fans shared designs online.

I spent a lot of time studying the community around Quake; I was amazed at the time people were pouring into making their own custom levels. So with The Sims, we wanted to make it possible to modify everything. Players could use it as a storytelling platform. At first, the stories were superhero, fantasy stuff. But as the demographics widened, we started getting stories with a message.

And a lot of the fans were non-traditional gamers, not 18- to 25-year-old males.

SimCity had far more female players than most games, by which I mean 20 percent, instead of five percent. But The Sims was predominantly female -- 55 or 60 percent. For a lot of them, it was the only game they played. Plus every few months, we'd come out with an expansion pack for about $30 (£20). So they were paying $10 a month for a game that was continually being expanded. That sounds like the subscription structure of later titles such as World of Warcraft -- which brings to mind 2002's Sims Online.The Sims Online was taking The Sims into a giant, shared world. It was kind of Darwinian: who can build the coolest place that the others want to hang out in? It lasted only a year, but it foreshadowed things like Second Life, social games such asFarmville -- social networking in general. I wanted the social structures to be as emergent as possible. Players organised into guilds. A group formed a vigilante mob, which became the Sims Online Mafia. There was a godfather, and it turned out to be the woman who managed the housekeeping staff at the Bellagio in Las Vegas. She obviously had organisational skills -- maybe even some familiarity with Mob tactics, I don't know. Next up was your gameSpore, which got a lot of attention for its ambition. Your creatures start microscopic. They become multicellular. The game moves on to the land, and they become more intelligent. They start having tribal structures, then building cities. They develop spaceflight, and eventually they're discovering other races, terraforming new planets. Now you've focused on Stupid Fun Club. It was originally a playground where we'd build funny, cool things. After I finished Spore, I decided to come to SFC full-time, at which point EA invested in it and it became more like a real company. What's the mission? Taking gaming sensibilities into new areas. Games have been at the front of crowd-sourcing and user-generated content. How do we make TV or whatever more interactive, so that the audience feels ownership? What will happen with games? I don't think anybody can look two years out and have a clue what the industry is going to look like, which is exciting. The social-gaming market is attracting the untapped group that The Sims found. That really broadens the types of games that we can create. Now, a game launches and people like one feature, so the developers tear the game up and build everything around that feature. It used to be that companies would commit years and millions of dollars to a game, then roll the dice and release it. Now it's: "Let's do it slowly based on audience reaction." We can get feedback within hours and change the game while they're playing. We can begin customising games for individuals. What would a game like that look like? Imagine Steven Spielberg talking to you, observing what you watched, and then going off to make a movie just for you. It's a little scary: we're talking about something potentially more addictive than any drug. Does this relate to games that Stupid Fun Club is developing now? I can't talk much about them, but one is about how to turn your life into a game. Your real life, not a virtual fantasy world. The other one is about taking all your digital content and making it feel tangible and playful, a window into the cloud of your stuff. You think data visualisation is going to play a bigger role in life? It's a literacy that people will start developing, now we're able to capture so much personal information. You're going to have an interest in interpreting that. It's about people finding ways to get insight into themselves.